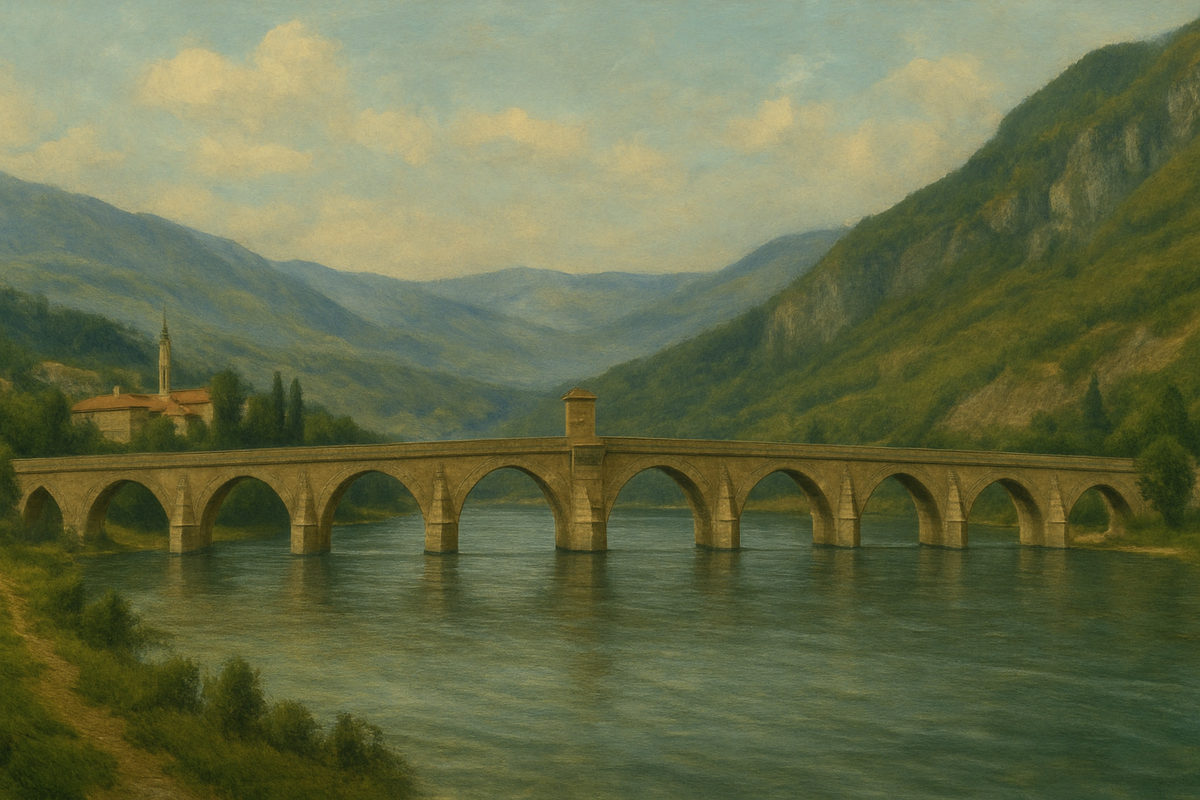

The Bridge on the Drina: A Chronicle Etched in Stone and Time

Elegant, resilient, scarred by time and conflict, yet still standing.

Some books seem to peer into your understanding of time, memory, and what it means to build something that outlasts us. Ivo Andrić's The Bridge on the Drina became that kind of book for me, a reading experience that shifted from simple appreciation to something approaching reverence as I turned its pages.

Having recently been to Bulgaria, I came to this Nobel Prize-winning novel with renewed curiosity about the Balkans' complex history, but what I found was something far more profound: a meditation on permanence and transience, on the structures we build and the stories they accumulate, on how history isn't an abstract force but something lived, suffered, and endured by ordinary people in extraordinary times.

When a Bridge Becomes a World

The novel centres on the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad, a small Bosnian town where the Drina River cuts through forested mountains. What struck me immediately was Andrić's audacity: this isn't the story of a person but of a structure, a magnificent stone bridge that stands witness to nearly four hundred years of human drama, from the zenith of Ottoman power in the mid-16th century to the catastrophic opening of World War I in 1914.

I'll admit, when I first understood the scope of what Andrić was attempting, I was somewhat sceptical. How could a bridge sustain a narrative across four centuries? How could stone and mortar become a protagonist? But Andrić, writing during the crucible of World War II, understood something essential: in regions where empires rise and fall, where populations collide and coexist, where history seems to move in violent lurches—perhaps only the land itself, and what we build upon it, can tell the full story.

Born from Violence, Built for Connection

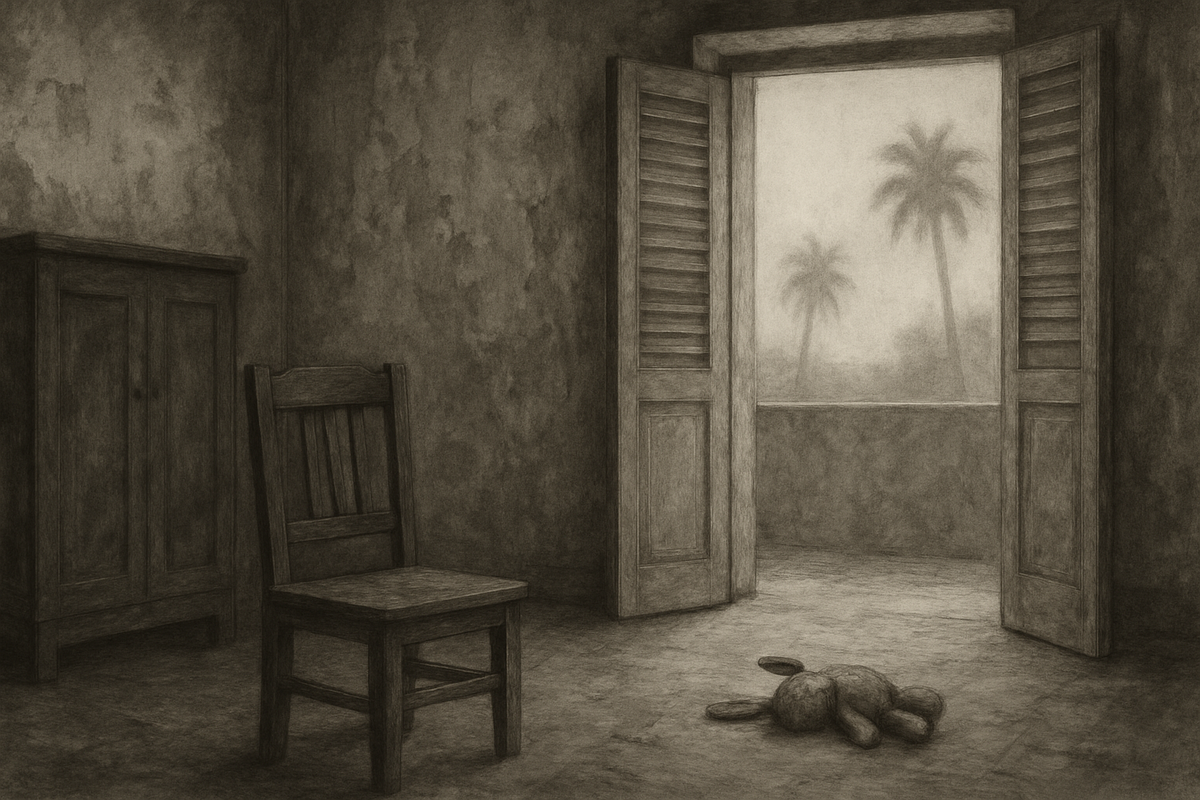

The bridge's origin story haunted me. It was commissioned by a man whose very existence embodies the region's painful complexities. Born a Serbian Orthodox boy named Bajica around 1505, he was torn from his family as part of the devşirme—the Ottoman "blood levy" that conscripted Christian boys for imperial service. His mother followed him, wailing, until they reached the Drina. There, at a ferry crossing, they were finally, irrevocably separated.

That boy, renamed Mehmed after converting to Islam, rose through extraordinary talent to become Grand Vizier, one of the most powerful figures in the Ottoman Empire. And what did he do with that power? He ordered the construction of a magnificent stone bridge—designed by the legendary architect Mimar Sinan—at the very spot where he'd been severed from his mother and his former life.

This apparent paradox stopped me in my tracks: a bridge meant to connect, to facilitate passage, born from the trauma of separation. A structure intended to unify, built by an architect of the very system that had violently assimilated its patron. And more—the construction itself, from 1566 to 1571, relied on local Serbian peasants conscripted into forced labour, men who sabotaged at night what they'd built during the day, seeing the bridge as a symbol of oppressive foreign might.

The brutal Ottoman overseer Abidaga responded with horrific cruelty, publicly impaling a captured saboteur named Radisav. Reading this scene—Andrić's prose stark and unflinching, almost clinical in its horror—I understood that he was showing us something fundamental: even our most beautiful creations arise from conflict, exploitation, and suffering. The bridge that would come to symbolise endurance and connection was steeped in division from its very first stone.

On Bridges Built from Separation

The irony is not lost on me—that I should find such resonance in a bridge born from violent separation, when my own life was shaped by another kind of bridge, equally paradoxical in its origins. The parallel strikes me with particular force. Mehmed Paša, torn from his mother at a river crossing, later builds a bridge at that exact spot of separation. The structure meant to unite emerges from the memory of being divided. Similarly, the aerial bridge that carried me from Luanda to Lisbon in my infancy was an instrument of connection forged by the very violence that necessitated it. Both bridges—one of stone spanning a river, one of aircraft spanning an ocean—share this DNA of displacement transformed into passage. More on that here:

What haunts me about Andrić's bridge is how it stands as testimony to survival through transformation. Built by the displaced for connection, it endures precisely because it serves a purpose larger than the trauma of its origins. The aerial bridge that carried me served its immediate function and then vanished, but its effects persist—not only in the way I understand home as provisional, identity as negotiated, and belonging as something constantly constructed rather than simply inherited, but also in how it shaped what would become a central preoccupation of my life: building bridges of understanding between people, institutions, and worlds that might otherwise remain separate.

Perhaps it's inevitable that someone torn from one shore and deposited on another would become, in adulthood, a builder of passages. My work in international academic partnerships, in facilitating student mobility across borders, in creating spaces where people gather to think critically about technology and human flourishing—all of it, I see now, carries the imprint of that early crossing. When I help establish Erasmus agreements or coordinate academic exchanges, I'm not just processing paperwork; I'm enabling others to cross their own divides, to experience the productive disorientation of being between worlds, to discover that identity can be additive rather than exclusive.

Even my writing—these essays that excavate memory, interrogate technology's effects on consciousness, explore how we maintain our humanity amid accelerating change—functions as another kind of bridge. I write not to settle questions but to create passages between the personal and the political, the individual and the structural, the remembered and the imagined. Each essay is an attempt to span some divide, to help me and any potential readers cross from one way of seeing into another, to make connection possible across gaps that feel uncrossable.

This isn't missionary work or redemptive narrative. I don't build these bridges to atone for colonial inheritance or to compensate for displacement. Rather, it's something more fundamental: having been carried across a divide at such a formative moment, having lived my entire conscious life in the space between origins and arrivals, I simply understand—in my bones, in my breath—that bridges matter. That connection is not natural but constructed. That passages must be built and maintained. That the work of spanning divides is never finished but must be renewed with each generation, each conversation, each attempt to reach across difference toward understanding. Those of us who cross bridges we didn't choose, who survive passages we cannot recall, carry within us both the wound of separation and an intuitive knowledge of connection's necessity. We become, almost despite ourselves, architects of the very thing we most needed: ways to get from one shore to another, structures that might help others navigate the crossings they too must make.

Perhaps this is why I find such power in Andrić's choice to centre not a person but a structure. Bridges outlast the traumas that birth them. They serve future generations who know nothing of the violence that necessitated their construction. They become, over time, simply what they are: means of passage, instruments of connection, places where life happens. The kapia, that widened platform where Višegrad gathered for four centuries, eventually transcended its origin story to become just... the place where people met.

This is what Andrić understood so profoundly: that the bridge is both wound and suture, both reminder of separation and instrument of reunion. For those of us who crossed our own bridges—aerial or otherwise—the paradox lives in our very bodies. We are here because we were torn away. We connect because we were divided. We build meaning from displacement.

The Heart That Never Stops Beating

As I navigated the novel's episodic structure, watching generations appear and vanish like ripples on the Drina, I began to grasp the bridge's true significance. It's the one constant in a world of flux, the silent observer that outlasts every human ambition and tragedy.

The kapia—the bridge's widened central platform—became my favourite element of the narrative. It functions as Višegrad's living room, its public square, where people gather to drink coffee and plum brandy, conduct business, play games, gossip, and watch the river flow. I could see it so clearly: men lounging on the stone benches, the murmur of conversation, the play of sunlight on water below. It's where life happens—proposals and arguments, celebrations and conspiracies.

But what moved me most was how Andrić uses the kapia as a barometer for the town's soul. During peaceful times, it's a space of genuine, if cautious, coexistence. Later, as nationalist ideologies seep into Višegrad, it becomes where students gather to debate conflicting visions of the future, where the community's fault lines become visible. The same stones that once supported neighbourly tolerance become a stage for ideological conflict.

The bridge accumulates stories like a stone accumulates moss. There's the tragic leap of beautiful Fata, escaping an unwanted marriage by jumping to her death. The ruinous gambling night of Milan Glasičanin. The legendary drunken dance of Salko Ćorkan along the narrow railing. But also darker memories: the impaled saboteur, severed heads of Serbian rebels displayed as warnings, the humiliation of the respected elder Alihodja, nailed by his ear to the bridge by retreating Ottoman soldiers.

Andrić captures this accumulation beautifully, observing that the bridge remains "clean, young and unalterable" even as it witnesses endless human suffering and joy. He writes: "Life is an incomprehensible marvel, for it is continuously wasted and spent, yet nonetheless it lasts and endures, like the bridge on the Drina." Reading those words, I felt the weight of what he was saying—about how our individual lives are fleeting, yet something persists, something endures through all our temporary dramas.

Empires Come and Go

One of the novel's great achievements is how vividly it renders the texture of daily life under different imperial systems. The Ottoman centuries are portrayed with remarkable nuance—not as monolithically oppressive or benevolent, but as a complex reality where people adapted, resisted, collaborated, and simply lived their lives under the weight of distant authority.

Then comes 1878 and the Congress of Berlin, and suddenly, Višegrad finds itself under Austro-Hungarian rule. I was fascinated by Andrić's portrayal of this transition through the character of Alihodja, the elderly Muslim shopkeeper who simply couldn't believe that "infidels" would ever rule his town. His story crystallises the shock of imperial transition: counselling against armed resistance yet unable to accept the new reality, he's nailed to the bridge by his ear by departing Ottoman loyalists, only to be rescued by the arriving Austrian soldiers. The indignity, the confusion, the collapse of his entire worldview—Andrić renders it with devastating clarity.

The Austrian period brings what we'd call modernisation: new infrastructure, a railway line to Sarajevo, hotels, barracks, trade unions, and new political ideologies. Foreigners arrive from across the Habsburg Empire. Lotte's hotel becomes a gathering place for this new, more cosmopolitan Višegrad.

But here's what troubled me, what Andrić seems to suggest with growing unease: this modernisation doesn't unite—it sharpens divisions. The railway diminishes the bridge's importance. Traditional rhythms are disrupted. New ideas—socialism, nationalism—ferment among students returning from universities abroad. The very infrastructure meant to integrate the region becomes, ultimately, the means of its violent fragmentation. When World War I erupts, it's the Austrians who mine the bridge, preparing it for destruction. The tools of connection become weapons of war.

A Tapestry of Humanity

What kept me engaged through nearly four centuries of narrative was Andrić's gift for creating vivid, achingly human characters who appear for a chapter or two, live their lives with all the intensity of believing themselves central to the universe, and then fade back into time's current.

Višegrad is a microcosm: Bosnian Muslims (many descended from local Slavic converts), Orthodox Serbs, Sephardic Jews, Roma, Catholics, and, under Austrian rule, a bewildering array of Habsburg subjects. These communities coexist—sometimes harmoniously, often warily, occasionally violently.

Reading their interactions, I was struck by how Andrić resists easy narratives. There are long periods of practical coexistence, shared spaces, and mutual dependence. The kapia hosts them all. Lotte's hotel serves everyone. Daily life creates a kind of working peace.

But underneath? Tensions simmer. Historical grievances persist. And when external pressures arrive—rebellions, imperial transitions, war—the social fabric tears with terrifying speed. Neighbours become suspects. The Serbian uprisings bring suspicion crashing down on the Orthodox community. World War I shatters everything, leading to arrests, hangings, forced evacuation, and spontaneous segregation along ethnic lines.

What haunted me was Andrić's implication: this coexistence is often pragmatic rather than deeply harmonious, a matter of shared geography and circumstance, vulnerable to the forces of history and identity politics. The unity isn't false, exactly, but it's fragile—a truth that resonates uncomfortably in our own fractured times.

I know this portrayal has sparked debate, particularly after the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s. Some critics worry the novel can be read as supporting narratives of inevitable "Balkan hatreds." But I think Andrić is doing something more nuanced—showing how imperial interventions and historical traumas create the conditions for conflict, not portraying hatred as some essential ethnic characteristic. In his Nobel acceptance speech, he spoke of seeking to understand conflicts "with reason and with a profoundly human spirit." That intention shines through, even in the darkest passages.

The Art of Witnessing Time

Andrić's literary technique itself became part of what moved me. This is epic historical realism, yes, but with a unique structure: episodic, almost like a series of interconnected short stories spanning centuries. Characters emerge vividly, play their role, and often disappear entirely, replaced by new generations facing new challenges.

At first, this structure disoriented me. Where was the protagonist I could follow? Where was the conventional narrative arc? But gradually I understood: the structure IS the meaning. The procession of transient lives across the permanent bridge embodies the book's meditation on time, mortality, and what endures. The form mirrors the content with elegant precision.

Andrić's narrative voice is peculiar—often detached, almost like a chronicler dispassionately recording events. The description of Radisav's impalement is so stark, so clinical, it made my skin crawl precisely because of its lack of melodrama. Yet this detachment coexists with moments of profound empathy and psychological insight.

I came to think of this narrative stance as adopting the perspective of the bridge itself—observing human affairs over centuries with a long-view serenity that encompasses both creation and destruction, joy and suffering, as parts of one continuous flow. It's an almost superhuman perspective, one that sees individual tragedies as threads in a larger tapestry.

The prose itself, even in translation, carries a poetic quality, a subtle rhythm that makes the reading experience feel simultaneously immediate and timeless. I found myself slowing down, savouring passages, rereading sentences that seemed to capture something essential about how we live in time.

Why It Still Matters

The Bridge on the Drina won Andrić the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1961, bringing recognition not just to him but to Yugoslav literature as a whole. The Swedish Academy cited "the epic force with which he has traced themes and depicted human destinies drawn from the history of his country." Andrić donated his entire prize to establish and improve libraries in Bosnia and Herzegovina—a gesture that seemed to honour the bridge's own purpose: creating infrastructure for connection and knowledge.

Reading it now, decades later and in our own fractured moment, I found the novel's themes disturbingly resonant. How do diverse communities coexist? What happens when historical traumas echo through generations? How does modernisation interact with tradition? What's the relationship between infrastructure and ideology, between physical connections and social division?

The novel doesn't offer easy answers. It's not a morality tale with clear lessons. Instead, it provides something more valuable: perspective. A deep immersion in the rhythms of time, in how history is lived on a human scale, in the ambiguous nature of our connections to each other.

A Bridge That Still Stands

Finishing the book, I sat for a long time thinking about that bridge—elegant, resilient, scarred by artillery fire in 1914, yet still standing. (The real bridge, remarkably, survived both World Wars and still spans the Drina today.)

It serves as a metaphor for so much: human creativity and its limits, the persistence of memory against the erosion of time, the ambiguous nature of connection—how the same structure that unites can also divide, depending on who's looking at it and when.

As previously mentioned, Andrić wrote this during World War II, watching his own world tear itself apart. In the bridge, perhaps he found something to hold onto—a reminder that humans build beautiful, enduring things even in the midst of brutality, that our creations can outlast our conflicts, that there's something noble in the very act of connection even when connection seems impossible.

Reading The Bridge on the Drina was, for me, an exercise in expanding my temporal perspective. We live in such immediate times, consumed by the urgency of the present moment. Andrić invites us to step back, to see how patterns recur, how quickly the urgent becomes historical, how what seems permanent crumbles and what seems fragile endures.

It's not an easy book. The episodic structure can be disorienting. The violence is stark and unsettling. The lack of a conventional closure for characters can feel frustrating. But these difficulties are part of what makes it profound. History doesn't offer neat resolutions. People don't always get satisfying endings. Yet life continues, and bridges stand.

If you're willing to surrender to its unique rhythm, to let it carry you across four centuries of human experience, The Bridge on the Drina offers something increasingly rare: a genuinely expansive vision, one that holds both the intimate and the epic, the beautiful and the brutal, the transient and the enduring in a single, encompassing view.

As Andrić suggested in his Nobel banquet speech, the storyteller's ultimate purpose should be to serve "man and humanity." His bridge still does that work, still connects us to the past, still reminds us of what we build and what we destroy, still stands as a testament to the complex, painful, magnificent story of how we try to live together across all our differences.

And somehow, improbably, beautifully, it endures.