Adrift in Barcelona: Unpacking Manuel Vázquez Montalbán's Southern Seas

It transcends genre conventions, using the framework of a detective investigation to offer what Montalbán aimed for across the series: a "moral chronicle" of Spain's tumultuous Transición, the period of transition from Franco's dictatorship to democracy in the late 1970s.

The title itself, Southern Seas (Los mares del Sur), conjures images of escape, of Gauguin’s vibrant Polynesian canvases, of a life lived far from the grey complexities of modern Europe. Yet, the central figure of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán’s celebrated 1979 novel, a wealthy businessman obsessed with precisely this dream, isn't found basking on a Tahitian beach. Instead, Carlos Stuart Pedrell is discovered stabbed to death on a desolate construction site in a working-class Barcelona suburb. This immediate, stark paradox—the yearning for an exotic paradise colliding with the grim reality of urban decay—sets the stage for a novel that is far more than a simple whodunit. It signals the book's deep engagement with the chasm between aspiration and actuality, a theme that resonates profoundly within its specific historical context.

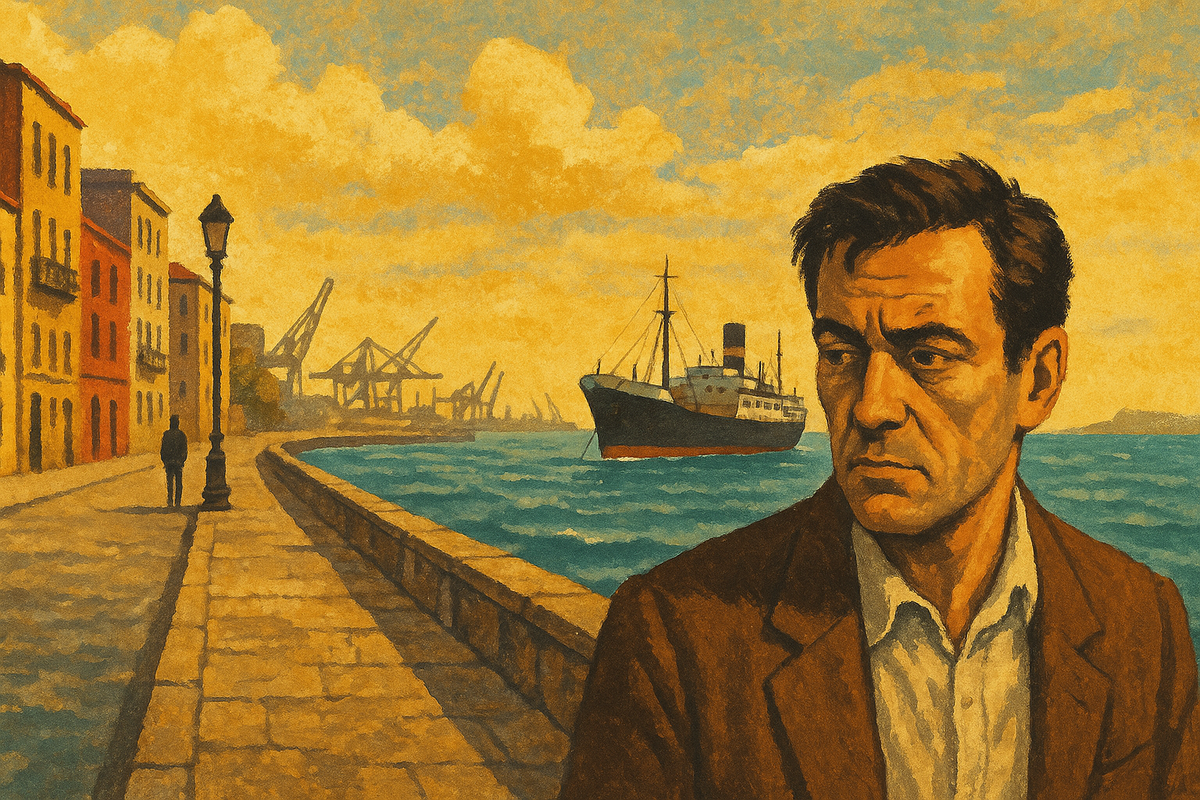

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán was a towering figure in modern Spanish letters – a poet, essayist, novelist, journalist, political commentator, and noted gourmand. His work is often infused with sharp social critique and political engagement, born from his own experiences as a leftist jailed under Franco. At the heart of his most famous creation is Pepe Carvalho, the protagonist of Southern Seas and a sprawling series that followed. Carvalho is no ordinary private eye. He is an icon of Spanish literature, a figure riddled with contradictions: a cynical, world-weary gourmand, an ex-communist who also served time as a CIA agent, a man of culture who notoriously burns books from his own library.

Southern Seas, winner of the prestigious Planeta Prize in 1979 and France's Grand Prix de Littérature Policière in 1981, is widely regarded as one of Montalbán's finest works and a cornerstone of the Carvalho series, even earning a place on El Mundo's list of the 100 best Spanish novels of the 20th century. It transcends genre conventions, using the framework of a detective investigation to offer what Montalbán aimed for across the series: a "moral chronicle" of Spain's tumultuous Transición, the period of transition from Franco's dictatorship to democracy in the late 1970s. The novel delves into the pervasive sense of disillusionment, the complexities of identity, and the jarring realities of a society caught between a repressive past and an uncertain future. The central paradox of Pedrell's fate—dreaming of the South Seas but dying in Barcelona—can be seen as a reflection of Spain's own national condition during the Transición. The collective aspiration for a bright, democratic, modern future often clashed with the messy, compromised, and sometimes deeply disillusioning reality of political deals, unresolved social tensions, and the lingering shadows of the old regime. Pedrell's personal failure to find his paradise mirrors the nation's struggle. This exploration seeks to navigate the murky waters of Montalbán's Barcelona, examining the intricate plot, the unforgettable protagonist, the richly textured historical backdrop, and the novel's enduring, albeit sometimes problematic, resonance from an informed, personal perspective.

The Mystery of the Man Who Dreamed of Tahiti

The narrative engine of Southern Seas is the perplexing death of Carlos Stuart Pedrell. He is presented as a man of considerable means and influence: a construction magnate, an eccentric patron of poets and painters, a dreamer captivated by the life and art of Paul Gauguin. A year before his body is discovered, Pedrell announced his intention to travel to the South Pacific, presumably to follow in his idol's footsteps. He vanishes, and everyone assumes he is living out his fantasy. The discovery of his corpse, brutally stabbed, not in Polynesia but on a neglected building site in a peripheral Barcelona neighbourhood, shatters this illusion.

Enter Pepe Carvalho. Hired by Pedrell's widow (acting through the family lawyer, Viladecans ), Carvalho's brief extends beyond simply identifying the murderer. His primary task, the one that drives the narrative, is to reconstruct Pedrell's missing year. Where was he? What was he doing? The investigation prioritises the victim's hidden life over the mechanics of the crime itself; the "why" and "where" eclipse the "who". This shift immediately signals Montalbán's intention to use the detective plot as a vehicle for deeper exploration.

Carvalho's investigation becomes a journey through the stratified social landscape of Barcelona. He moves between the opulent but emotionally frigid world of the city's elite—Pedrell's cold wife, seemingly more concerned with wealth than her husband's fate, and his circle of friends, preoccupied with maintaining appearances —and the starkly contrasting "inframundo de los suburbios," the underworld of the suburbs. His search leads him to a working-class barrio, a newly constructed, somewhat soulless neighbourhood on the city's edge.

There, Carvalho uncovers Pedrell's secret: the magnate hadn't fled to the South Seas at all. He had been living a double life, renting a modest apartment and posing as an ordinary accountant. The trail eventually leads Carvalho to Ana Briongos, Pedrell's young, pregnant lover, a politically active worker from the local SEAT car factory who knew her lover only as the humble accountant, completely unaware of his immense wealth and status. The tension between these two worlds—the privileged, decaying elite and the struggling, pragmatic working class—animates the novel's core conflicts. By structuring the plot around the unravelling of the victim's identity and motivations, Montalbán cleverly subverts the expectations of the detective genre. The crime becomes less a puzzle to be solved and more a catalyst for social diagnosis and the deconstruction of a life lived between illusion and reality. The investigation itself serves as a scalpel, dissecting the layers of Barcelona society and the complex psyche of the man who dreamed of escape but found death at home.

Pepe Carvalho: An Appetite for Truth (and Everything Else)

Pepe Carvalho stands as one of modern crime fiction's most distinctive and compelling protagonists. He embodies certain archetypes of the genre—the cynical, world-weary private investigator navigating the moral ambiguities of a corrupt city —drawing comparisons to figures like Philip Marlowe. Yet, he is profoundly, uniquely Spanish, or more specifically, Catalan, deeply rooted in the culture, politics, and, famously, the cuisine of Barcelona.

His character is defined by its "rich, complex and contradictory personality". This isn't mere character colour; it's fundamental to his function within the narrative and his reflection of the era. His past is a tapestry of opposing threads: a former communist militant jailed under Franco, he also paradoxically worked for the CIA. He possesses a "vast culture", yet engages in the shocking ritual of burning books from his own library, perhaps as kindling, perhaps as a gesture of profound disillusionment with intellectualism. He can appear "phlegmatic" but pursues his investigations with dogged determination, even while seeming perpetually tired, a man questioning his own endurance. Physically described as overweight, balding, and prone to excessive drinking, he nonetheless exerts a powerful, if perplexing, attraction on women.

Carvalho's Contradictions

This deliberate construction of Carvalho as a walking paradox is central to Montalbán's project. His internal contradictions mirror the external ambiguities and compromises of the Transición itself. This period in Spanish history was defined by the uneasy coexistence of old Francoist structures and new democratic aspirations, by ideological realignments, and by a pervasive cynicism born from the perceived failures of grand political narratives, both from the Left and the Right. Carvalho, with his communist past and CIA entanglements, his intellectualism and his book-burning nihilism, embodies this societal schizophrenia. He is post-Franco Spain in miniature, wrestling with its fragmented identity and disillusionment.

Perhaps the most famous of Carvalho's traits is his obsessive passion for gastronomy. Food and drink are constants in his life and in the novels, often described with meticulous, almost ritualistic detail – from making a shrimp omelette to preparing elaborate dinners. This isn't mere local colour. In a world marked by moral decay, political corruption, and intellectual uncertainty, Carvalho's engagement with cuisine offers a connection to the sensual, the immediate, the tangible. Cooking and eating become acts of grounding, rituals that provide structure and pleasure amidst the surrounding chaos. It can be read as a personal system of value, a way of finding meaning and reaffirming life when larger political and social systems seem bankrupt or treacherous. It might even function, as one analysis suggests, as an "artifice that masks our essential savagery". Some critics note, however, that his consumption can seem almost "mechanical", lacking the "sublime appreciation" found in characters like Andrea Camilleri's Inspector Montalbano (who was, incidentally, named in homage to Vázquez Montalbán ).

Carvalho functions explicitly as a social critic, the "thermometer of the established morality". His investigations provide a platform for "precise and biting descriptions of Spanish society", cutting across all social strata from the privileged elite to the marginalised working class. His own outsider status—son of immigrants, with a radical past —lends credibility to his critical perspective.

However, Carvalho is far from a straightforward hero. His character attracts significant criticism, particularly regarding his treatment of women. His relationship with Pedrell's vulnerable, drug-using teenage daughter, Yes, whom he sleeps with and mocks, is often cited as deeply problematic. His attitude towards other female figures, including the activist Ana Briongos and his long-term companion, the prostitute Charo, is described by some reviewers as involving "undeserved sneering". Readers have found him "cold", a "jerk", self-absorbed, and his appeal to women a "male fantasy". These critiques highlight a dimension of the character that sits uneasily with contemporary sensibilities, complicating his role as a moral arbiter.

Barcelona, 1979: A City Between Dictatorship and Democracy

In Southern Seas, Barcelona in 1979 is not merely a setting; it is an active participant in the narrative, a complex character in its own right, embodying the tensions and contradictions of Spain's Transición. The novel is precisely located in this pivotal year, on the eve of the first municipal elections after Franco's death, a moment pregnant with both hope and apprehension.

Montalbán masterfully uses the city's geography to depict its social stratification. The narrative moves between the luxurious enclaves of the established bourgeoisie, like the Sarrià-Saint Gervasi district, and the harsh realities of the periphery. Pedrell's body is found in a "run-down tenement block" or a depressing, newly built satellite town like the fictional San Magín – a place representative of real dormitory towns like Bellvitge, where working-class families, often immigrants from other parts of Spain, struggle to pay off mortgages on their small apartments, their "agujero" (hole). Pedrell's secret life, lived between these two extremes, underscores the deep social fissures running through the city.

The weight of the recent past hangs heavy over this urban landscape. Carvalho encounters a Barcelona described as "fossilised and brittle", still bearing the deep scars of Franco's long dictatorship. Characters frequently reflect on the Franco era, sometimes with a conflicted nostalgia ("With Franco, what happens today didn't happen" ), revealing the tangled nature of memory and political adjustment in the Transición. The wealthy elite, many of whom prospered under the old regime, now face the uncertainties and potential challenges of democracy with apprehension.

Montalbán leverages this setting for potent social commentary. The novel critiques the realities of class struggle, the often-destructive impact of capitalist development, including unchecked urban planning and land speculation, and the precarious conditions of the working class, represented by characters like Ana Briongos and her fellow workers at the SEAT factory. The narrative diagnoses a pervasive "cultural malaise" affecting the city and, by extension, the nation. The city itself is presented as a space where social inequalities are not only reflected but actively reproduced and reinforced.

This mapping of social conflict onto urban geography suggests a deeper point. The physical fragmentation of Barcelona—the stark divide between the privileged center and the marginalised periphery—serves as a powerful spatial metaphor for the fractured social and political reality of the Transición. The novel implies that the shift to democracy has not necessarily healed these divisions. In fact, the forces of neoliberal development, represented by figures like Pedrell himself, may be exacerbating them, creating new forms of alienation and segregation. The inability of Pedrell to truly belong to or escape either world, ultimately meeting his end in the liminal, unfinished space of a construction site, reinforces the sense that these societal fractures are profound and perhaps intractable, casting doubt on the unifying potential of the new democratic project.

Illusions and Disenchantment in Post-Franco Spain

The recurring motif of the "Southern Seas" and Paul Gauguin serves as the novel's central metaphor for escape and the yearning for an idealised existence. For Carlos Stuart Pedrell, it represents a flight from the perceived emptiness of his bourgeois life, a quest for authenticity and "vital plenitude, dreamed of and unrealizable". This personal dream of escape mirrors a collective desire within Spanish society during the Transición – an escape from the constraints and traumas of the Francoist past towards a freer, more fulfilling future. However, Pedrell's ultimate failure to reach his imagined paradise, his creation instead of a hidden, alternative life within the confines of Barcelona itself, powerfully underscores the theme of unattainable aspirations. The Southern Seas remain a distant, ultimately illusory, horizon.

This failure connects directly to the pervasive atmosphere of desencanto—disillusionment—that characterised much of the Transición period. The initial euphoria following Franco's death and the establishment of democracy gradually gave way to a sense of cynicism as the realities of political compromise, economic difficulties, lingering corruption, and the persistence of old power structures became apparent. In Pepe Carvalho, I see a reflection of that deeply human sentiment, one that settles into our bones when the world we believed in begins to crumble around us, a particular kind of collective disappointment that follows the collapse of grand dreams and promises.

There's something achingly familiar about Carvalho's cynicism, the way he looks at society and sees only rot beneath the surface. His declaration that people no longer believe in anything resonates with moments in my own life when I've witnessed communities lose faith in institutions, ideals, or movements that once held such promise. It reminds me of conversations with older relatives who lived through periods of dramatic social change, their voices carrying that same weight of betrayal and lost hope.

What strikes me most profoundly about this portrayal is how Montalbán uses Carvalho to explore the aftermath of transformation. The novel doesn't just critique the present moment; it mourns the gap between what was hoped for and what actually emerged. The reference to the "failed utopian leftist project" speaks to something I've come to understand through my own exploration of history and human nature—how even our most noble aspirations can become distorted or prove insufficient when faced with the complexities of real-world implementation.

Through Carvalho's disenchanted eyes, we're invited to confront an uncomfortable truth: that sometimes the very transitions we hope will liberate us can leave us feeling more lost than before. His cynicism becomes a mirror, reflecting not just Spain's particular moment of desencanto, but the universal human experience of reckoning with the distance between our dreams and our reality.

The novel also explores profound crises of identity, both individual and collective. Pedrell's elaborate double life is the most obvious manifestation, reflecting a man fractured and unable to find meaning or reconcile the disparate parts of his existence. He is described as a "narcissistic sufferer," incapable of handling maturity. Carvalho himself, with his contradictory allegiances and cynical worldview, represents another form of fragmented identity. Even younger characters, like Pedrell's daughter Yes, adrift in grief and seeking a sense of self, reflect the broader societal search for a stable identity in the wake of dictatorship.

The theme of reality versus aspiration runs consistently through the narrative. Pedrell aspires to the romantic escape of Gauguin but ends up murdered in a grim suburban reality. Spain aspires to the ideals of modern European democracy but remains entangled in the contradictions of its recent past and the challenges of the present. Carvalho might aspire to detached observation but finds himself inevitably drawn into the messy lives of others. Montalbán relentlessly exposes the gap between the seductive allure of dreams and the often-disappointing texture of reality.

Ultimately, the novel suggests the futility of seeking escape through geographical relocation or romantic fantasy. Pedrell's journey demonstrates that the sources of dissatisfaction are often internal—rooted in personal character flaws —and systemic—embedded within the social and economic structures from which one cannot easily break free. His failure to find solace either in his wealthy milieu or his fabricated working-class existence implies that the problems he faced were inescapable. This serves as a critique of romantic escapism, suggesting that genuine progress requires confronting the complex, often disillusioning realities of the present, rather than chasing mirages on a distant horizon. The Southern Seas, in Montalbán's vision, are not a destination, but a symptom of a deeper malaise.

Noir Seasoned with Irony and Cuisine

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán skillfully adapts the conventions of American hard-boiled and noir fiction—the legacy of writers like Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, whom he clearly admired —to the unique social and political landscape of post-Franco Spain. Southern Seas is exemplary of his approach: it utilises the structure of a detective investigation but elevates it into a sharp picture of Spain during a crucial moment in its history. His work is characterised by a potent blend of crime plotting, political commentary, and nuanced social observation, establishing him as a key figure in the development and international recognition of Spanish detective fiction.

A defining feature of Montalbán's style is his pervasive use of irony and satire. This manifests in witty, often scathing, portraits of characters representing different social types (such as the aristocratic Marqués de Munt) and in a sophisticated, self-aware attitude towards the very genre he employs. In a notable metafictional flourish, Carvalho stumbles upon an academic lecture dissecting the tropes of noir fiction, allowing Montalbán to simultaneously deploy and gently mock the conventions he uses. This self-reflexivity adds a layer of intellectual depth and signals the author's ambition to create something more complex than a standard mystery. I find myself drawn to the profound way Montalbán navigates the delicate balance between honoring literary tradition and forging his own creative path. There's something deeply moving about how he approaches the noir genre—not with reverence that borders on paralysis, but with the kind of confident self-awareness that comes from truly understanding both the form's power and its potential pitfalls.

When Montalbán acknowledges and even gently mocks the tendency to over-interpret noir's symbolic weight, he's doing something I recognise from my own journey with creative expression. He's claiming his space as both student and master, showing readers that true artistic maturity lies not in blind adherence to convention, but in the wisdom to dance with genre expectations while remaining authentically oneself.

This approach resonates with me because it reflects a kind of intellectual courage—the willingness to engage deeply with established forms while maintaining enough critical distance to see their limitations. Montalbán invites us into a relationship with his work that is both appreciative and knowing, where we can celebrate his technical mastery while recognizing his ability to transcend the very boundaries that might otherwise confine him.

Take gastronomy as an example. As previously noted, it is not just a thematic element but a crucial component of Montalbán's stylistic signature. The frequent, detailed descriptions of food preparation and consumption—from simple tapas to elaborate meals like shrimp omelettes or multi-course dinners —lend a unique sensory texture to the novels. This focus on cuisine provides character insight, anchors the narrative in tangible experience, and carries significant thematic weight.

The overall prose style is often praised for its blending of styles, its authority and compassion, and a tone sometimes likened to the "sorrow" present in John le Carré's works. However, the writing can also incorporate jarring elements, including descriptions of sex deemed "trashy" by some readers and an undercurrent of coldness that can be off-putting. Furthermore, linguistic analysis highlights how Montalbán uses language style, including vocabulary and patterns of speech, to delineate social class and ideological positioning, particularly evident in the portrayal of working-class characters, although the effectiveness of this can vary in translation.

Strengths, Shadows, and Personal Takeaways

Southern Seas stands as a significant achievement in contemporary Spanish literature, yet its legacy is complex, marked by undeniable strengths and persistent criticisms. Its power lies in several key areas. Montalbán conjures a palpable atmosphere, vividly rendering Barcelona at a critical juncture in its history, making the city itself a memorable character. The creation of Pepe Carvalho is a major literary accomplishment; he remains an iconic, uniquely contradictory figure who continues to fascinate and provoke. The novel's incisive social commentary on the post-Franco era, its exploration of class dynamics, political corruption, and widespread disillusionment, remains sharp and insightful. Furthermore, the work is admired for its intellectual depth, its skilful plotting, its distinctive blend of noir conventions with irony and gastronomy, and Montalbán's overall storytelling ability.

However, the novel is not without its shadows. The most significant and recurring criticism concerns its portrayal of women and what many perceive as a deeply ingrained misogyny. Carvalho's interactions with female characters, particularly his predatory relationship with the young and vulnerable Yes, are frequently cited as problematic, even "cringe"-worthy. This aspect feels particularly dated and jarring to contemporary readers. Beyond this specific issue, some find the overall tone of the book "cold" and struggle to connect with the characters, viewing Carvalho as self-absorbed or simply unlikable. The narrative's heavy focus on Carvalho's internal world and his culinary pursuits, while distinctive, might also be seen as detrimental to the pacing or the development of secondary characters. For readers seeking a conventional, plot-driven mystery, the deemphasis on the "whodunit" aspect can be frustrating. Finally, while generally well-regarded, the quality of translations can also impact reception, with some readers finding fault, and linguistic nuances related to class and identity potentially being lost or altered.

From a critical perspective today, I believe Southern Seas remains a powerful and important novel. Its exploration of disillusionment, the complexities of societal transition, and the search for meaning in a morally ambiguous world feels remarkably resonant. Carvalho, despite his flaws, is an unforgettable creation, a perfect guide through the labyrinth of post-Franco Spain. The atmosphere of Barcelona in 1979 is rendered with unforgettable detail. Yet, it is impossible to ignore the problematic aspects, particularly the treatment of women, which reflects attitudes that are unacceptable by today's standards. The novel's enduring high regard, despite these significant flaws, speaks volumes about the compelling force of its social critique, its atmospheric richness, and the magnetic pull of its central character. It prompts a necessary conversation about how we engage with literature from different eras, balancing historical context with contemporary ethical concerns, and acknowledging that literary merit and moral complexity often coexist uneasily.

Is Southern Seas Still Worth the Voyage?

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán's Southern Seas is undeniably a landmark of modern Spanish literature and a cornerstone of European crime fiction. It offers far more than a conventional mystery, serving as a vital, often biting, social chronicle of Spain during the critical years of the Transición. Its enduring value lies in its evocative portrayal of a specific time and place, its unflinching exploration of political and personal disillusionment, and its introduction of the unforgettable Pepe Carvalho – cynical, gourmand, contradictory, and utterly compelling. The novel's unique blend of noir sensibility, sharp irony, and rich sensory detail, particularly its focus on gastronomy, creates a reading experience unlike any other.

Its relevance persists. The themes of disillusionment with political promises, the search for identity in times of flux, and the tension between aspiration and reality are timeless. For readers interested in understanding Spain's recent history, the novel offers invaluable, albeit fictionalised, insights. Its influence on subsequent writers, including Andrea Camilleri, further cements its importance.

However, I would add this as advice to prospective readers: approach Southern Seas with awareness. It is not a light read, nor a straightforward detective story. Its pacing can be contemplative, its focus often internal. More significantly, its portrayal of women reflects attitudes of its time that are likely to be jarring and offensive to many contemporary readers. This is a crucial caveat.

I highly recommend Southern Seas, not as escapist entertainment, but as a challenging and deeply rewarding literary immersion. It demands engagement with its complexities, both stylistic and thematic, and requires grappling with its uncomfortable aspects. For those willing to undertake the voyage, it offers a rich, atmospheric, and intellectually stimulating journey into the heart of a specific historical moment and the soul of one of crime fiction's most enduringly complex figures. It remains essential reading for anyone serious about modern Spanish literature or the evolution of the noir genre in Europe.